Hulme and Moss Side Trail

Follow the route below!Welcome to the Hulme and Moss Side Heritage Trail!

Follow our heritage trails around Hulme and Moss Side, and discover the places where local activists stood up and fought for the rights of their communities. Each loop - our Orange Loop through Hulme and our Blue Loop through Moss Side - takes around 90 minutes to complete, but feel free to dip in and out and take it at your own pace!

The walk points

Stop 2: Moss Side People’s Centre

Stop 3: Moss Side Precinct

Stop 4: The Old Birley Tree

Stop 5: The NIA Centre

Stop 6: Church of the Ascension Sanctuary

Stop 7: Hulme Library and Hulme Community Arts

Stop 8: Hulme Crescents

Stop 9: The Zion Centre

Stop 10: Aaben Cinema, North Hulme Addy and Leroy James Park

Stop 11: The PSV Club

Stop 12: Hideaway Youth Club

Stop 13: The Reno and The Nile

Stop 14: West Indian Sports and Social Club

Stop 15: Mosscare and Great Western Street

Stop 16: Robert Lizar Solicitors

Stop 17: The Phil Martin Centre

Stop 18: Alexandra Park

Stop 19: Nello James Centre

Stop 20: George Jackson House

Stop 21: The Windrush Millennium Centre

Stop 1: Kath Locke Centre

The Kath Locke Centre was the first primary care centre in the country to be run by a local community organisation. Built by the NHS, it was initially campaigned against by local people who felt it was being imposed on them.

Eventually, the NHS decided to tender it out and the community group running the Zion Community Resource Centre took it over in 1996. They named it after Kath Locke as it symbolised what they thought was important – community activism and self-help.

In the summer of 2025, an exhibition launched at the Kath Locke Centre, telling the story of activism, protest and community spirit in Moss Side and Hulme. Pop in and take a look, and grab a drink and a sweet treat at the centre’s cafe to set you up for the rest of this trail!

Who was Kath Locke?

Kath was born in Manchester in 1928 and was an active member of Moss Side community politics, campaigning for Black history to be taught in schools, and persuading Manchester City Council to commemorate the 1945 Pan-African Congress with a plaque on the wall of Chorlton Town Hall.

She also campaigned against the poll tax, which had a disproportionate impact on the incomes of poorer people and fought to end the circulation of educational materials that stereotyped and disenfranchised Black people.

She was active in the Moss Side Housing Action Group and a founder member of the Abasindi Co-operative.

Stop 2: Moss Side People’s Centre

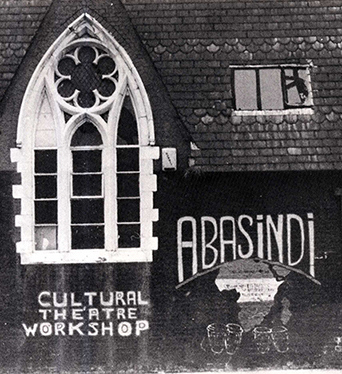

The Moss Side People’s Centre housed two of the most well-known projects to be developed in the area – the Family Advice Centre and the Abasindi Co-operative.

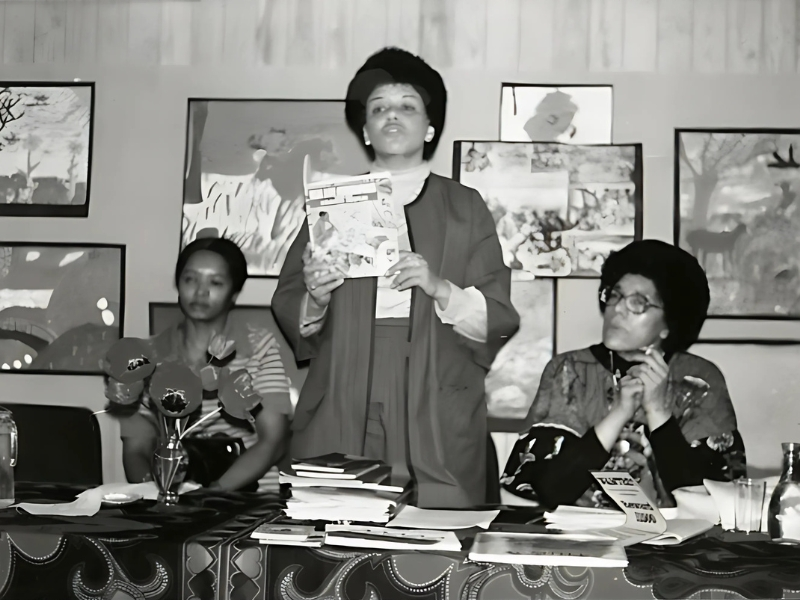

The Abasindi Co-operative was launched in 1980, as a self-help women’s organisation for Black women in Manchester.

Within a few years, this co-operative was leading a variety of community projects out of the Moss Side People’s Centre, ranging from health support, youth engagement and supplementary education.

Meanwhile, the Family Advice Centre, run by people from the local community, offered wide-ranging advice and support to local people, especially those who, for various reasons, were reluctant to use formal statutory services, often having been let down by them in the past.

The People’s Centre played a central role in the formation of the Moss Side Defence Committee in the aftermath of the uprisings in 1981, aiming to defend young Black people and convey a more accurate version of events than that put forward by the police and the press.

The committee argued that at the uprisings were a response to the actions and perceptions of the Greater Manchester Police within the community, coupled with the Thatcher government’s authoritarian law and order agenda.

The Stop and Search laws of the time gave the police the discretionary power to stop, search and, if deemed necessary, arrest people on suspicion of loitering with an intention of committing an offence, in breach of the Vagrancy Act.

The People’s Centre building is now the site of Rekindle School Manchester, an innovative, radical space that aims to rekindle a love of learning in young people disengaged with their education.

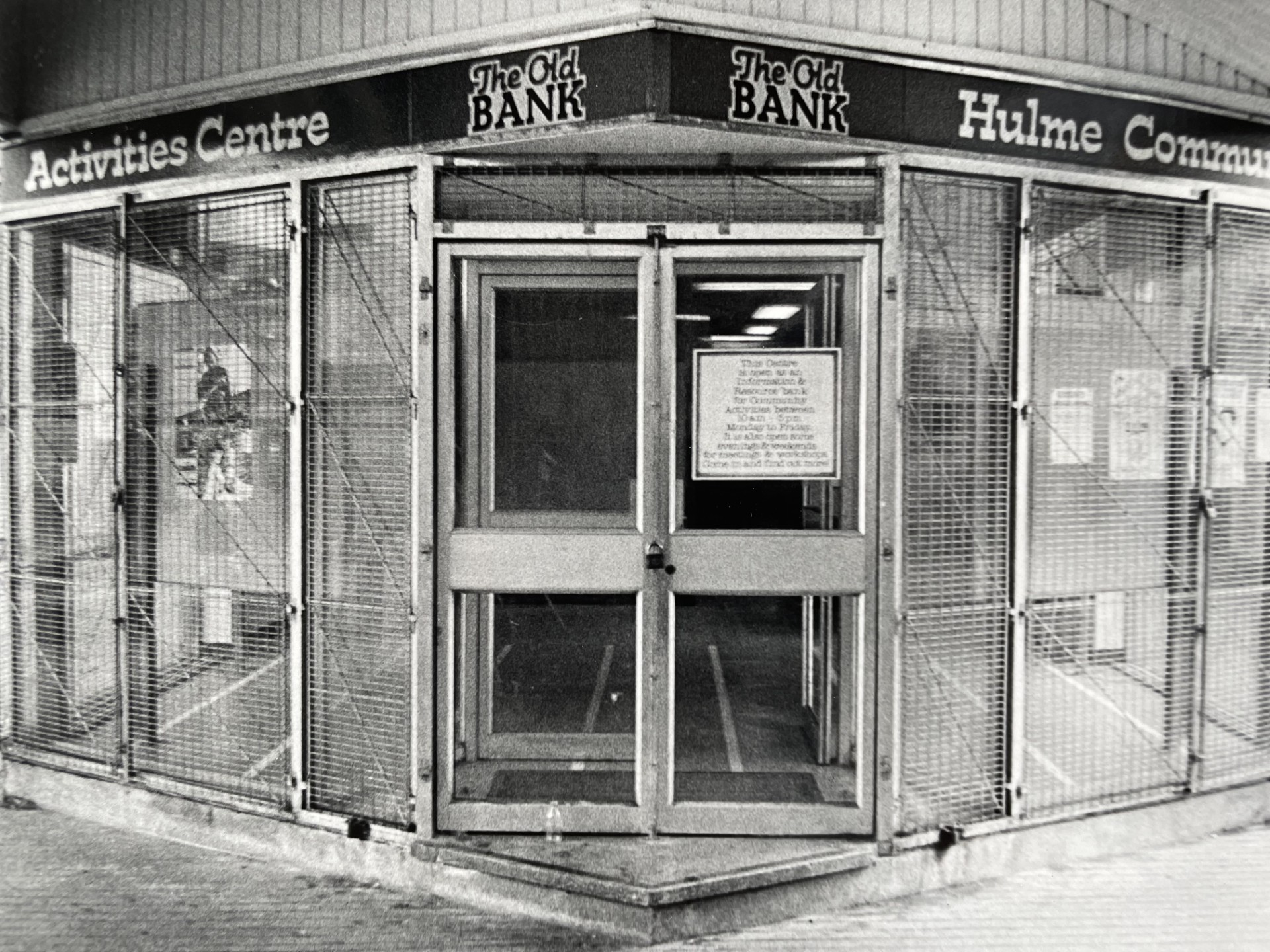

Stop 3: Moss Side Precinct

Moss Side Precinct was the heart of Hulme and Moss Side. It was where everyone met and shopped together.

Nestled between Gretney and Lingbeck Crescents, it had the housing office, a market, a launderette, banks, a post office and a host of community education and training services. These included 8411, a community education project which offered parents courses to return to education and, most importantly, a crèche for their children to be cared for while they were learning. In addition, the area was home to Moss Side Library, a youth support project and the Agency for Economic Development.

The shopping centre was demolished along with Lingbeck and Gretney, and replaced by Asda. A new Hulme High Street was created with a new indoor market – originally meant to be styled on French markets with fresh produce.

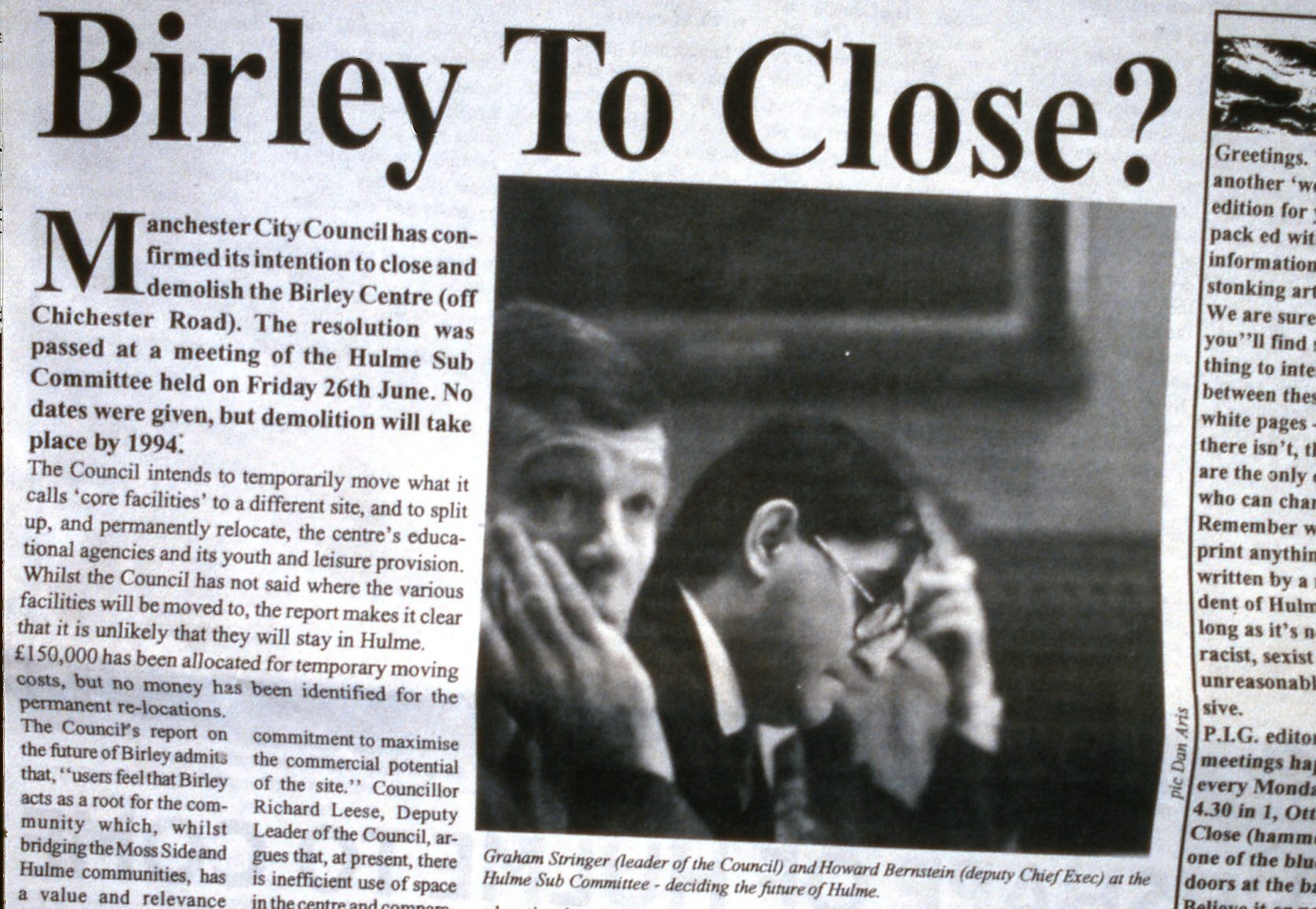

Stop 4: The Old Birley Tree

The Birley Tree grew on the site of the old Birley School, which became an Adult Education Centre. The school held an annual Roots Festival and took young people on a school trip to the Caribbean.

There was a campaign against the school’s closure, and against the destruction of the tree itself. The tree – the oldest in Hulme – became the focus of a campaign when it was going to be cut down for the site to be built on.

Two applications for a Tree Preservation Order were refused on the grounds that it was in decline, diseased and hollow; but a consultant and fellow of the Arboricultural Association declared the tree to be healthy; in fact, they called it an important specimen with at least another 25 years life.

The petitions, the campaign, and the strength of local feeling to keep the tree was a symbol of a community fighting for a different vision of the city, and that spirit continues with two key social enterprises nearby.

Over the road, Hulme Garden Centre was set up by two local residents on a derelict piece of land who were given a five year lease while the area was regenerated. It is now a successful social enterprise.

Nearby, Homes for Change is a community co-operative developed by local people during the regeneration of Hulme in the 1990s who wanted a more communal lifestyle. It is a lasting example of what people can achieve if they come together.

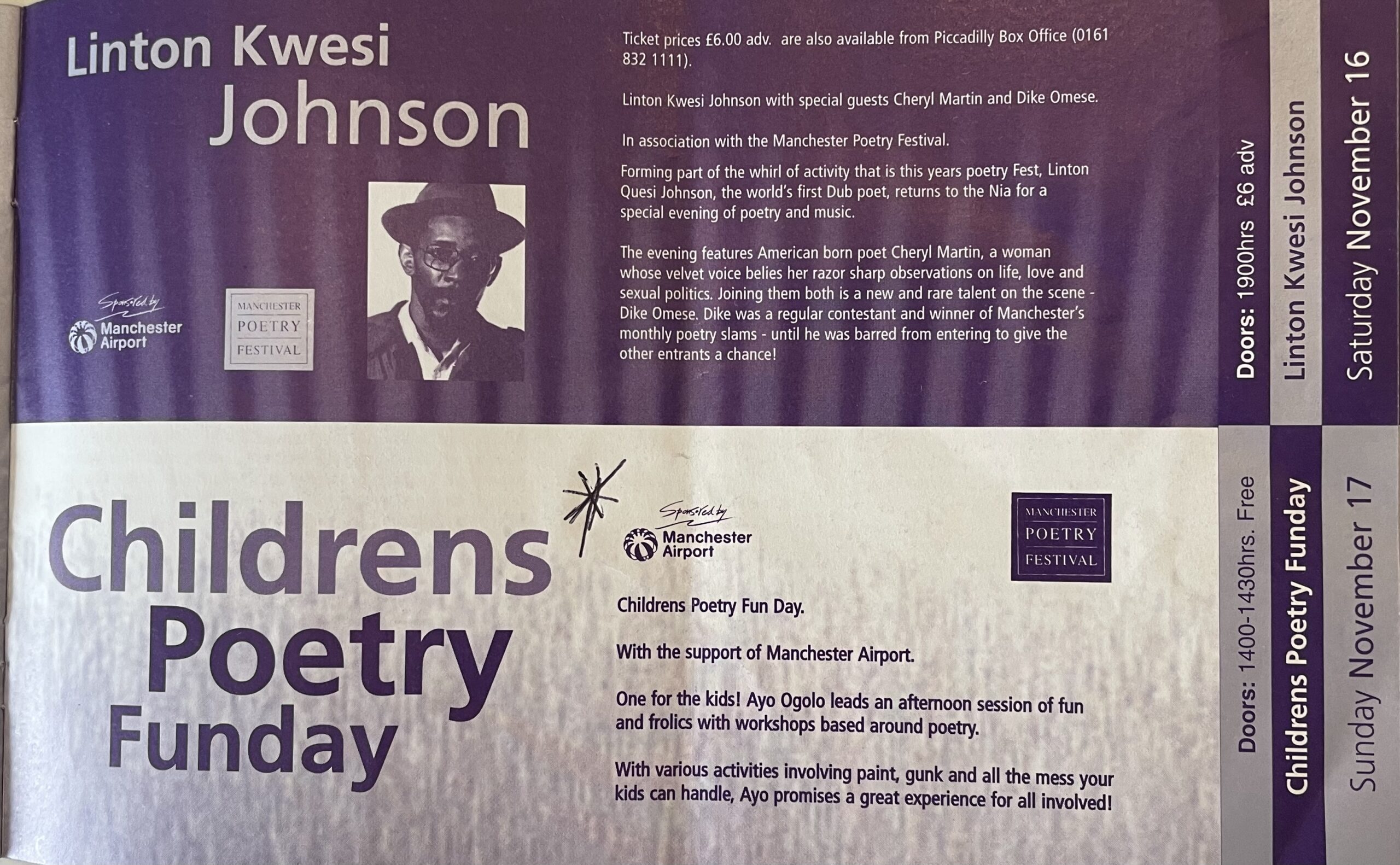

Stop 5: The NIA Centre

The idea for the NIA Centre has its roots in the rich tradition of Black culture that exists in Manchester. Based on the motto ‘a people without a knowledge of its history is like a tree without root, the NIA Centre was established in December 1986 in the BBC Playhouse in Hulme.

Five years later, in 1991, the iconic singer Nina Simone stepped foot into the NIA Centre to perform a gig that would embed itself in the rich cultural history of Manchester.

A global forerunner in the advancement of civil rights, Nina Simone sang song after song that reflected on the racial inequalities present across the world, in a venue at the heart of a community so well-versed at actively tackling this social injustice.

The building was originally known as the Hulme Hippodrome, opening on 6 October 1902. It was designed to look like a factory from the outside to ‘fit in’ to the industrial working-class community at the time.

In 1956 it was bought by the BBC and used as a venue for television and radio shows. The biggest names in music turned up at the centre – none more so than The Beatles, who made their radio debut there on March 7, 1962.

It is now the Niamos Centre, a community arts venue.

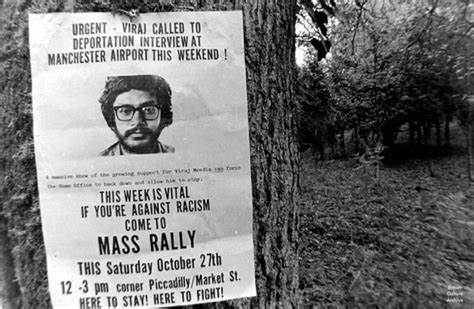

Stop 6: Church of the Ascension Sanctuary

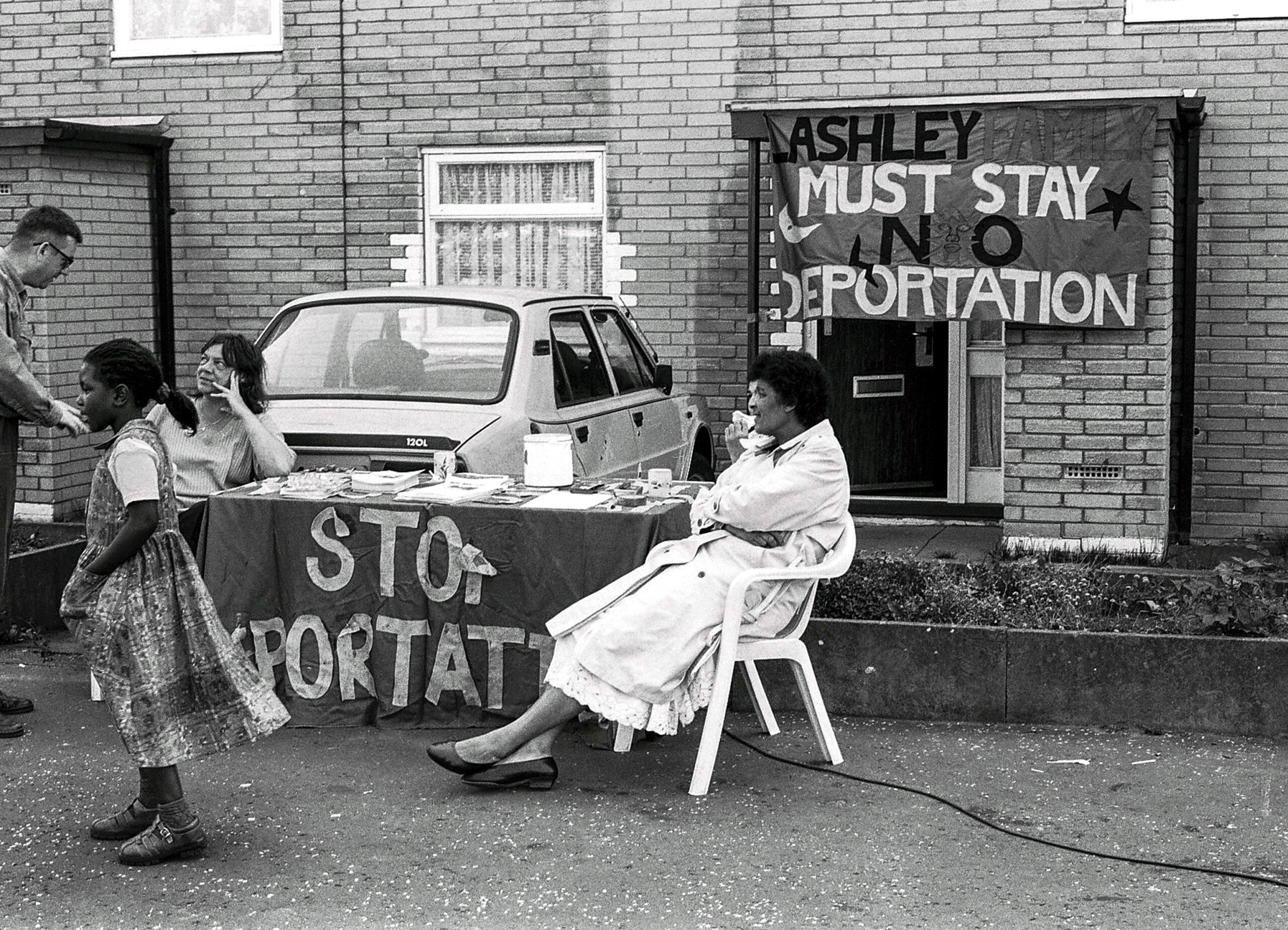

The Church of the Ascension still shows the scars of the battle to provide sanctuary to Viraj Mendis – a Sri Lankan seeking refuge in Manchester.

Iin 1986, Viraj lost his legal battle over his right to stay in Britain, but vicar John Methuen allowed him sanctuary in his Church of the Ascension.

A huge campaign developed, as Viraj stayed at the church for more than two years. The campaign successful delayed his deportation and ensured he was able to find safety in another country.

The door on inside the church still shows the marks of the battering ram where a team of 50 immigration officers forcefully broke in and arrested him in 1989.

Stop 7: Hulme Library and Hulme Community Arts

On the side of the District Centre (the site of the old Hulme Library), you’ll find a pottery mural telling the story of the area and its people.

This was created by Hulme Community Arts, who also produced many of the banners that local people used in protests and campaigns on the issues that mattered to them. They also supported people to express their views through news publications such as the Hulme Pig and The Octopus.

Tools such as these helped local people successfully campaign against the closure of Hulme Library. Although the original building is now a council district office, the library remains in the Moss Side Sports Centre.

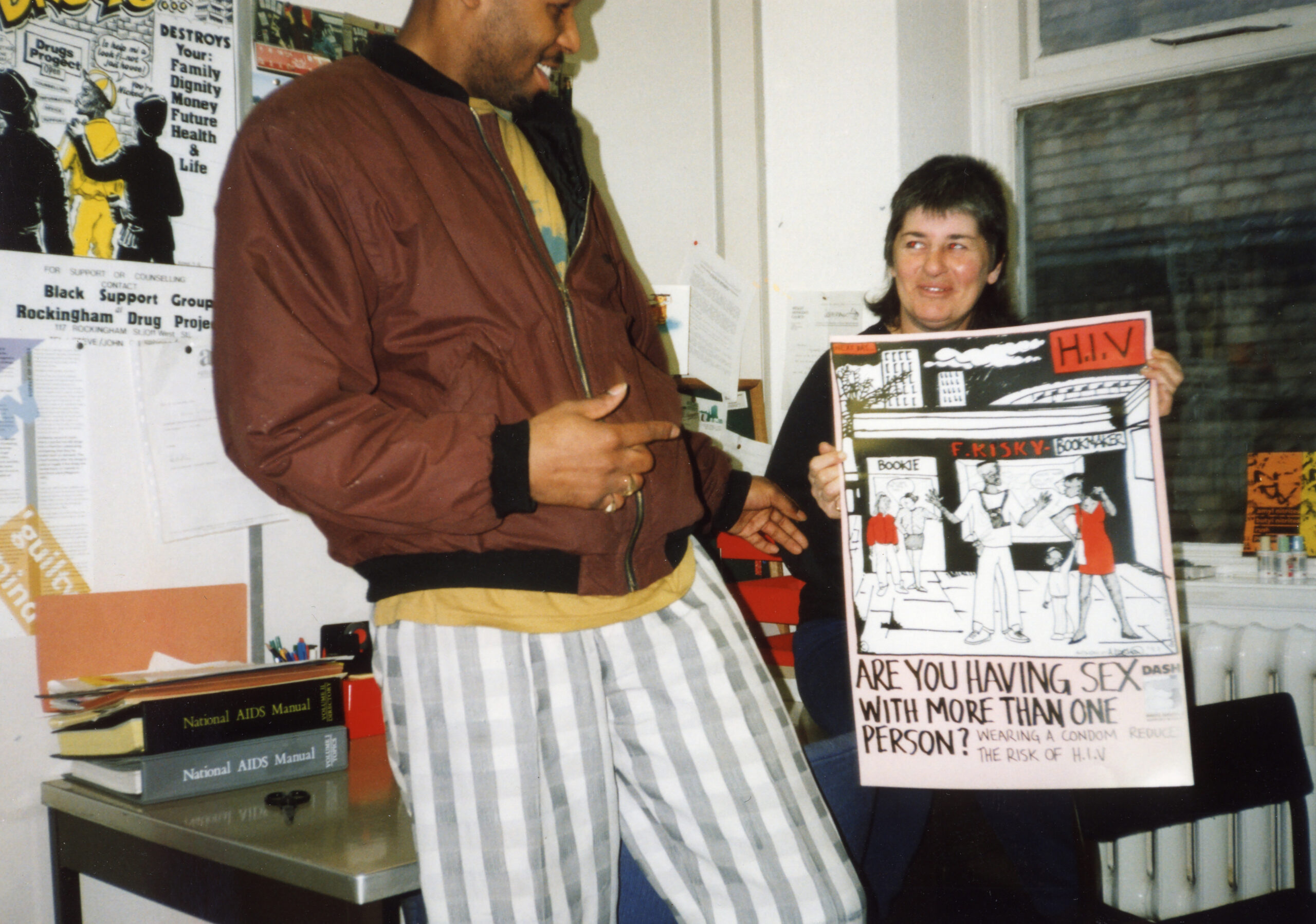

On nearby Clopton Walk, the first community needle exchange was set up in an old Direct Works store, providing clean needles, sharp boxes, condoms and harm reduction advice in the face of a growing Aids epidemic in the 1980s.

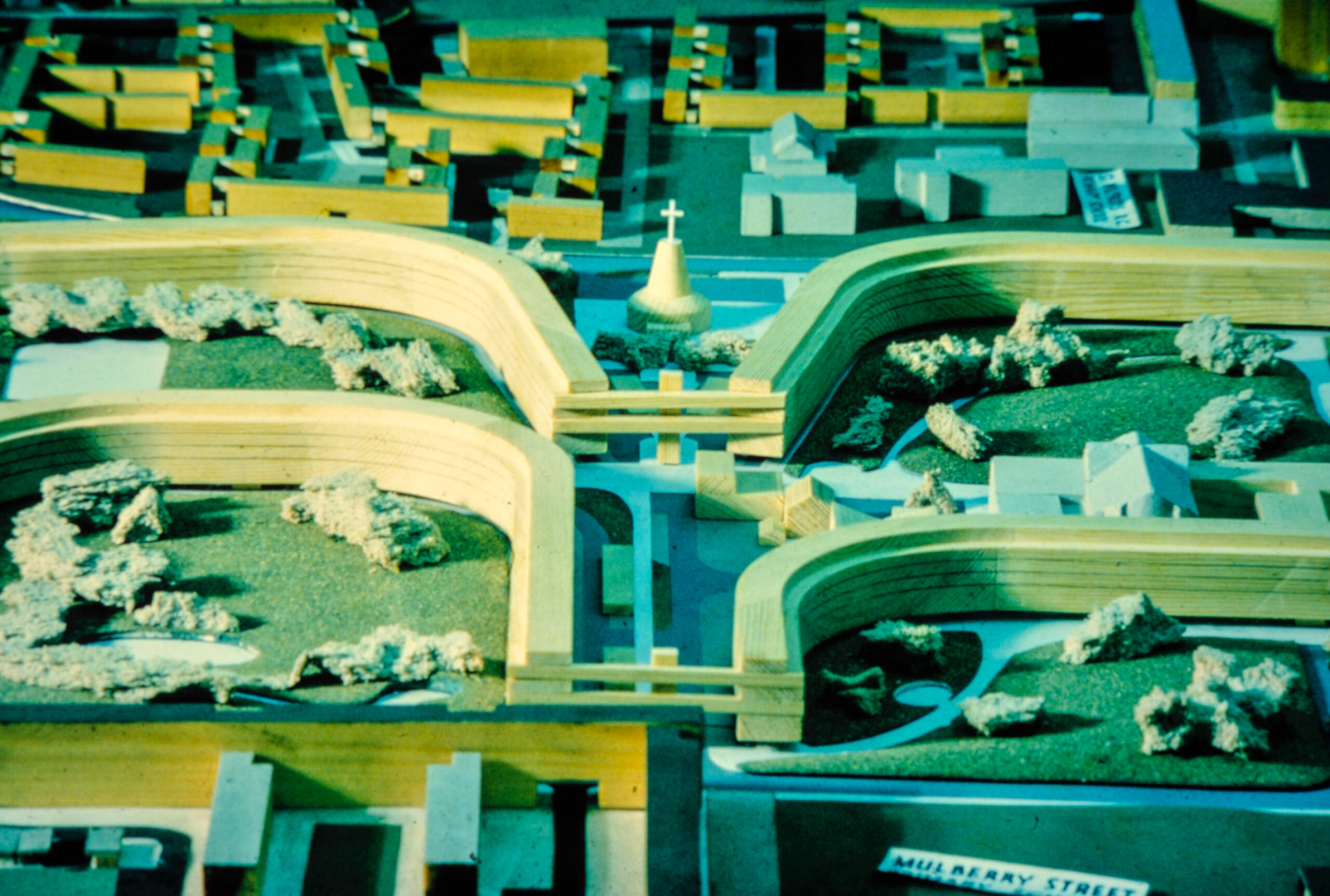

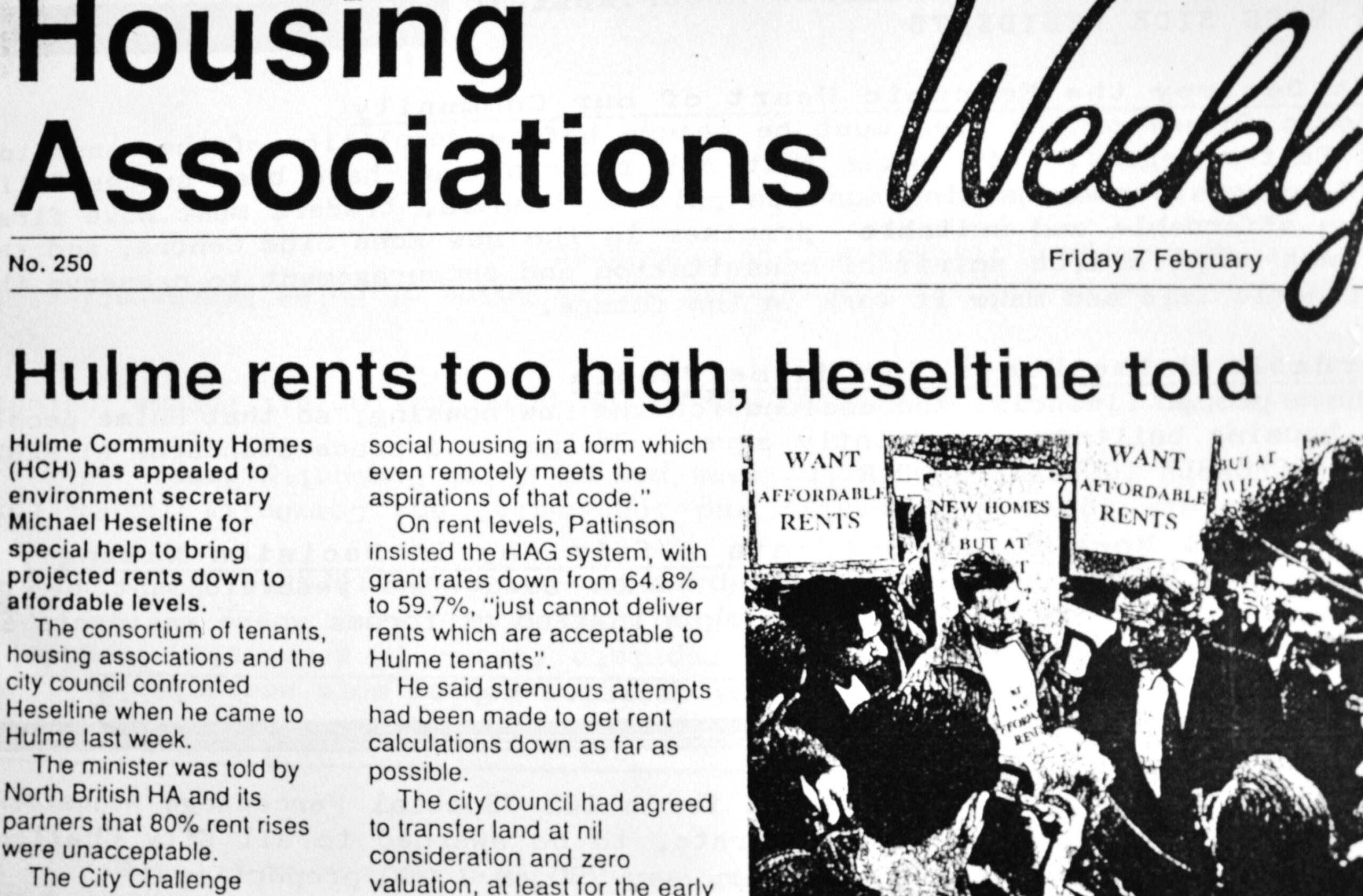

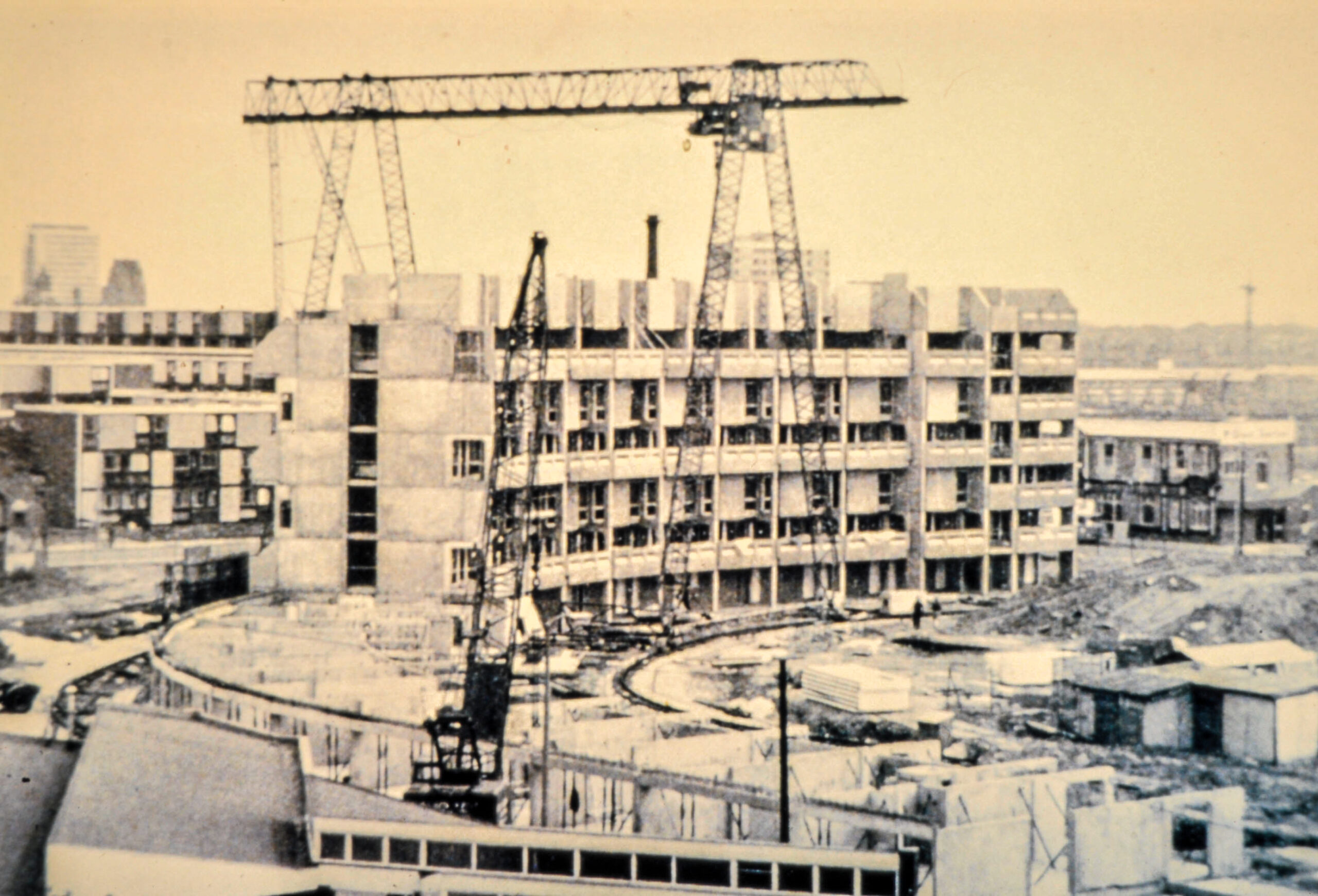

Stop 8: Hulme Crescents

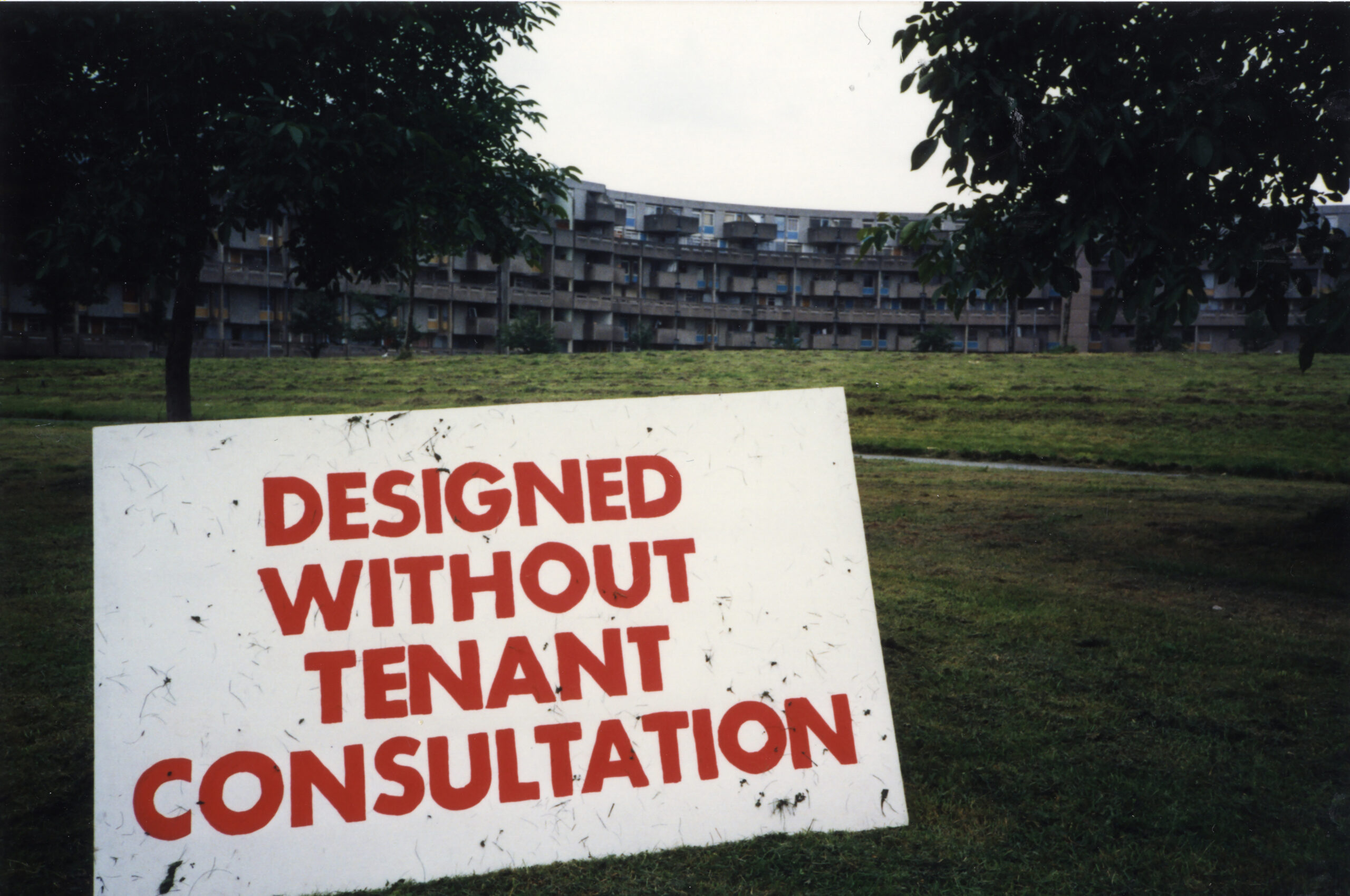

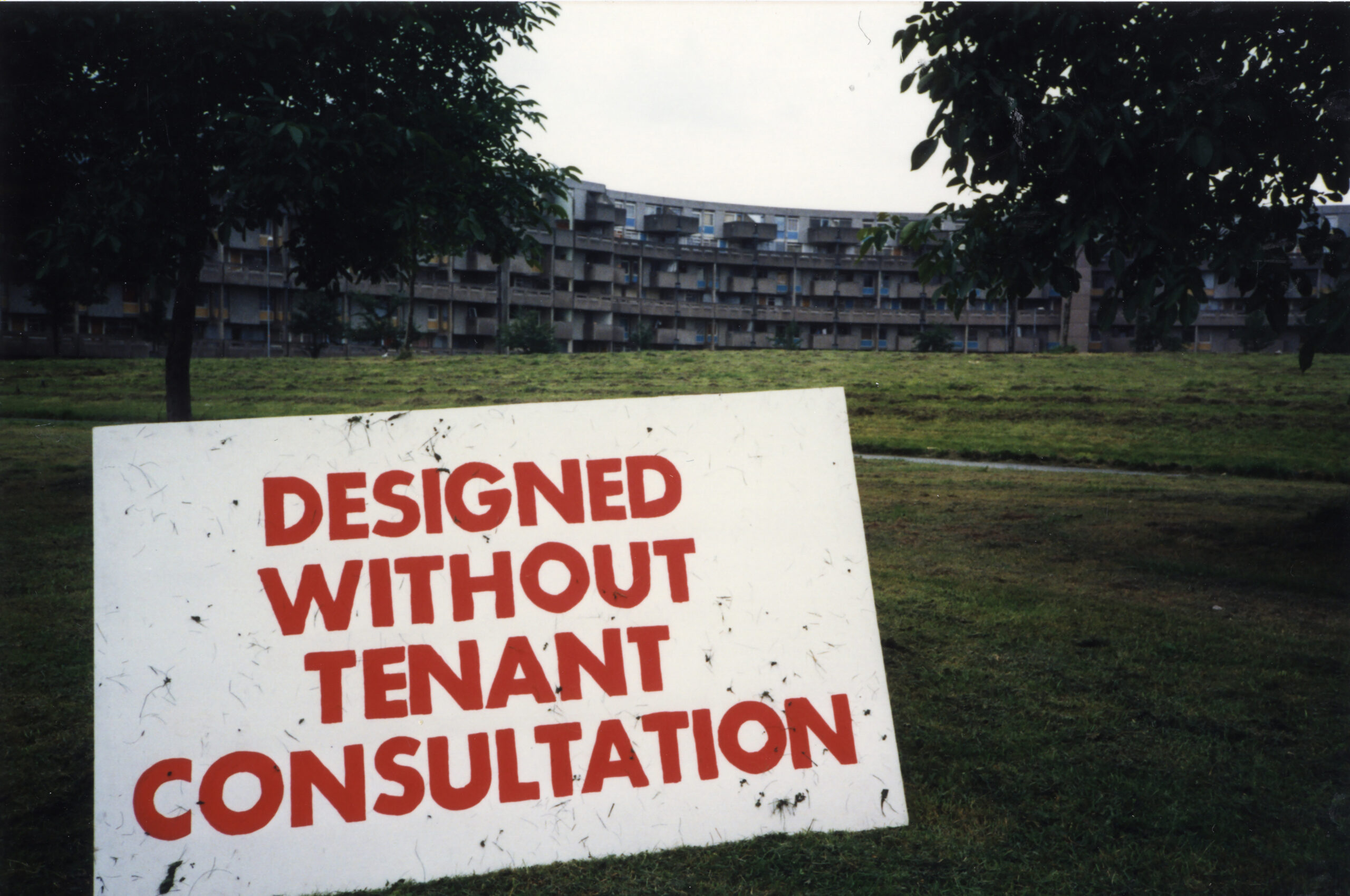

The Hulme Crescents were built in the 1970s as idealistic new homes, but they quickly showed problems with cracking concrete, mice and cockroach infestation, and disrepair.

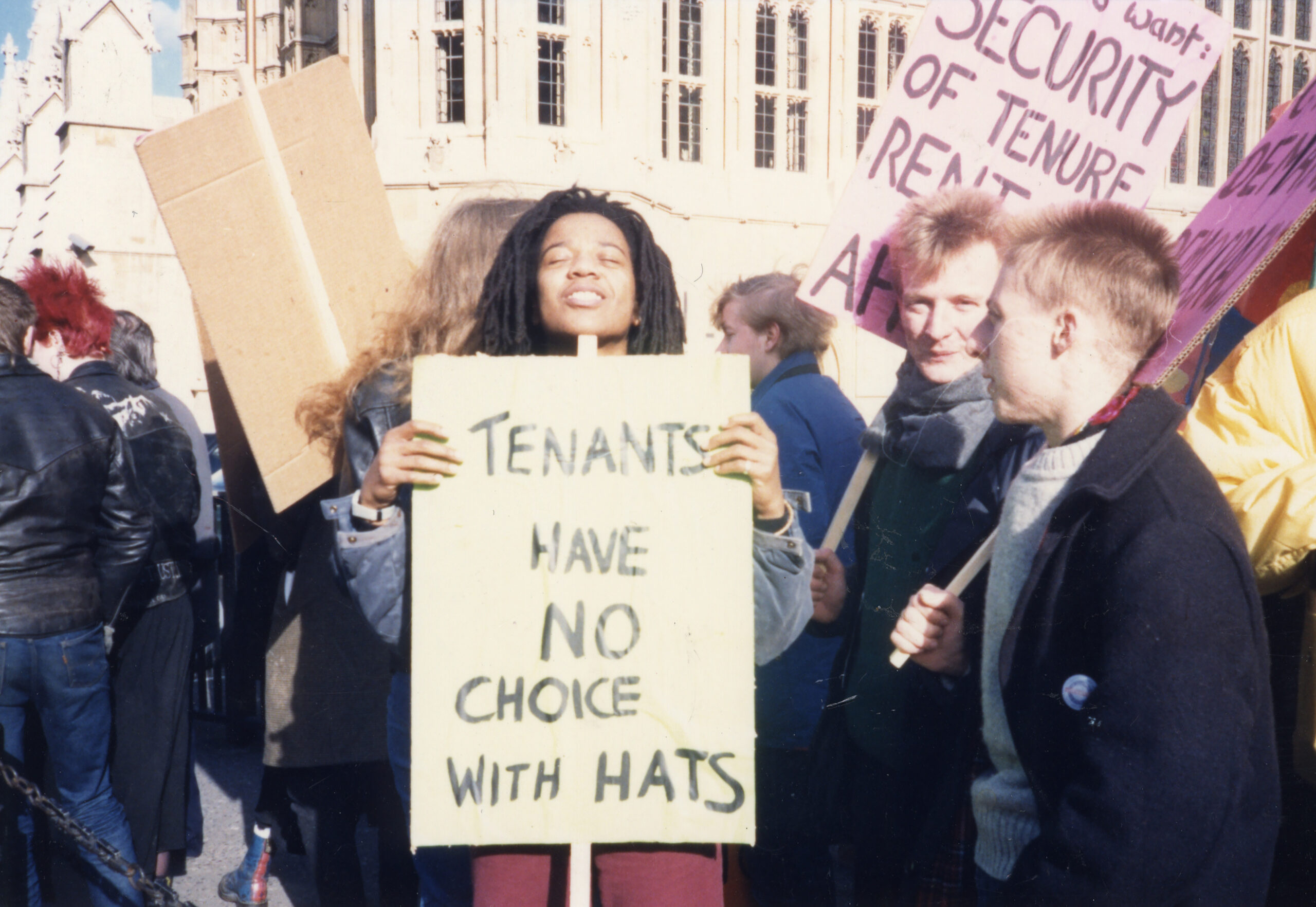

The Hulme Tenants’ associations actively campaigned for new homes for people in the area, designed with their involvement.

If you take a look around Hulme Park, which now occupies space that was previously in the middle of The Crescents, you’ll find a series of plaques that tell the story of the history of the area.

Stop 9: The Zion Centre

The Zion Institute was originally built by the church at the turn of the 20th century to provide services to the Hulme community, including a ‘poor man’s’ lawyer and a soup kitchen, before being transferred to the council.

By the 1980s it was home to the Halle Orchestra, who practiced there. However, the community campaigned for it to be returned to community use, and in 1991 the Zion Community Resource Centre started in the back of the building.

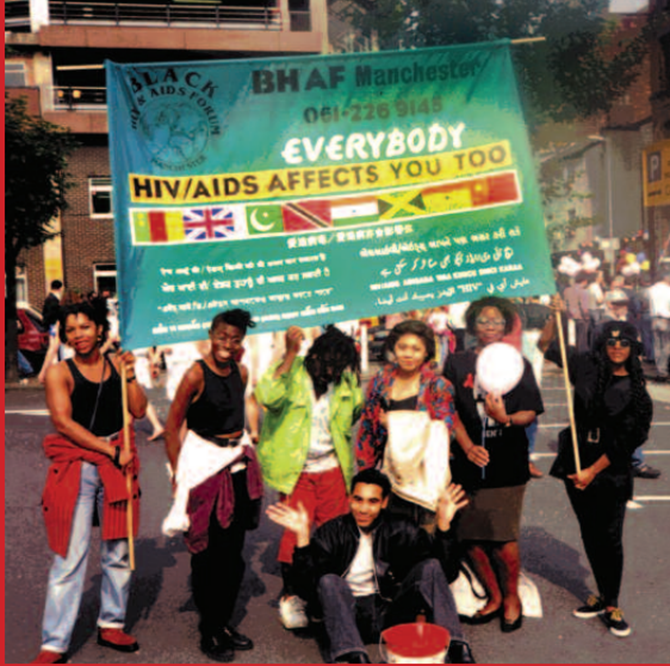

The community centre was created with a wide range of local voluntary groups, such as the Black Health Agency, African Caribbean Mental Health Services, Hulme Action Research Project (HARP), Drugs Advice and Support in Hulme (DASH), and Aisha Childcare.

Stop 10: Aaben Cinema, North Hulme Addy and Leroy James Park

The Aaben Cinema opened in 1928 and closed in 1991. Over the years it was the place to go to see films and in the later years became focused on alternative and art films.

Just off Jackson Crescent, the North Hulme Adventure Playground (known locally as The Addy) was the second such space to be built by the local community who wanted to provide outdoor play and activities for their children.

It was the second adventure playground to be built in the local area, after Moss Side Addy. Eventually there were six adventure playgrounds across Manchester, and it led to the creation of the charity ‘Young Lives’.

The spirit of local people setting things up for themselves continues to this day; within a couple of minutes of here, you’ll find St Wilfrid’s Enterprise Centre and Wesley Furniture Project, both set up by local people to provide jobs and training.

The Leroy James park was originally built on Leaf Street, in commemoration of two boys who drowned in the canal. During the most recent redevelopment of the area, it was planned to close, but thanks to community campaigning it was relocated to Hulme Park, where it remains today.

Directions to Aaben Cinema, North Hulme Addy and Leroy James Park

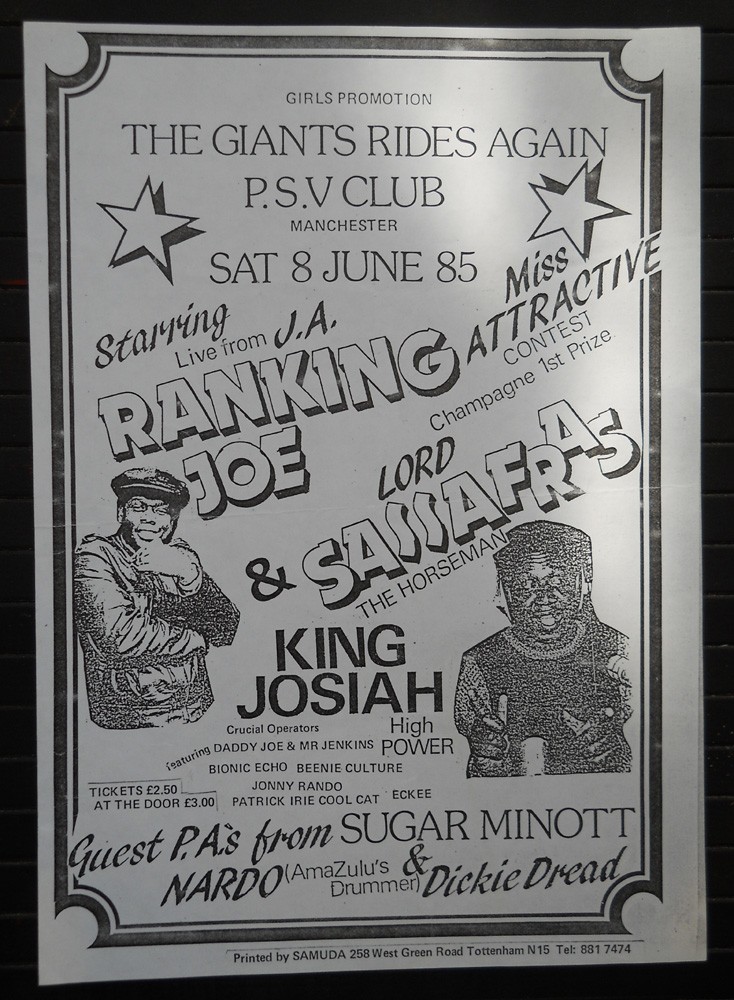

Stop 11: The PSV Club

The PSV (Public Service Vehicles) Club in Hulme had cultural significance; founded in the 1970s, The PSV Club was initially set up by members of the Jamaican community who worked as bus drivers in Manchester.

During the 1970s, it was home to The Factory, the influential night set up by Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus, which became the catalyst for Factory Records and The Hacienda.

In its later years, the PSV hosted many gigs and music nights before being closed in the early 1990s, prior to its demolition.

Stop 12: Hideaway Youth Club

Hideaway Youth Club is the oldest youth club in Manchester, opening in 1965 and supporting generations of families in the Moss Side community.

Over time, it was refurbished and transformed from a windowless building with a negative reputation, to a building where positive activities supported young people to thrive.

One of the highlights at the Hideaway was the ‘summer play schemes’, which provided activities such as camping in the countryside and taking day trips.

Hideaway aims to provide high quality youth work in a safe and secure environment where relationships and trust are developed and cherished, where young people have a voice and are heard, where difference is celebrated and where everyone works together to develop the full potential of all.

In 2020, Unity Radio broadcast A Moss Side Story, shining a spotlight on the Hideaway and taking you inside the project to meet some of the youth workers and young people that go there.

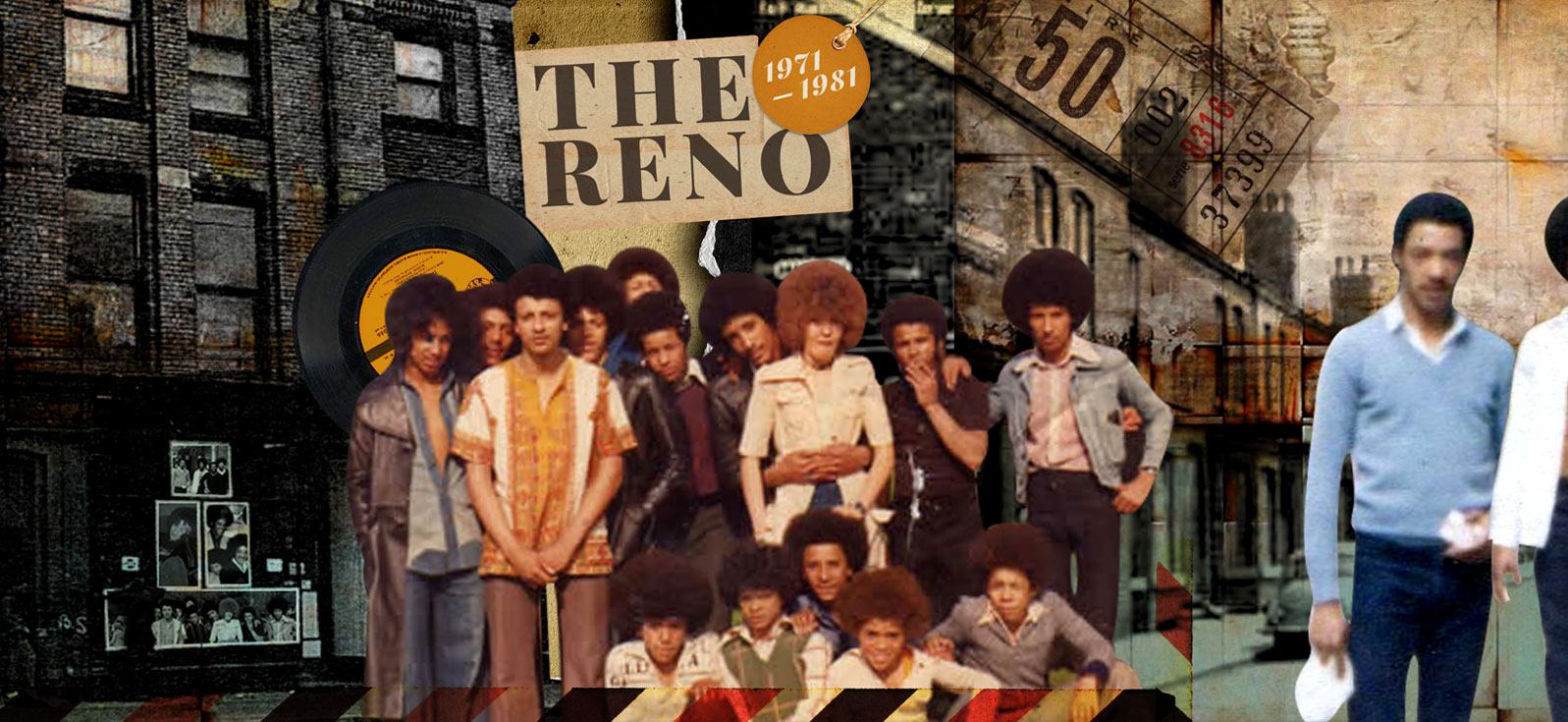

Stop 13: The Reno and The Nile

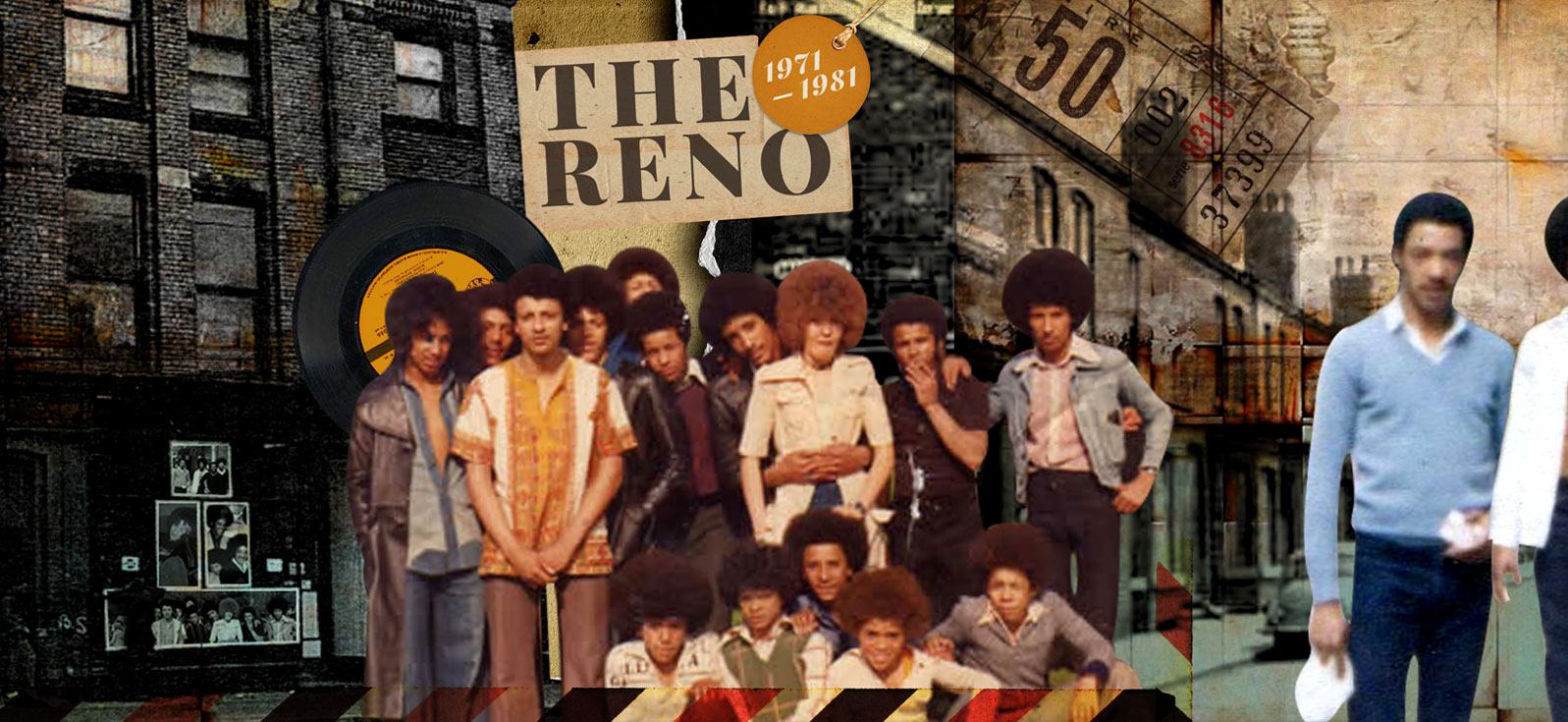

The Reno was started by Phil Magbotiwan in 1962, initially as a Salvation Army hostel for African seamen. Before then it was a club called “The Palm Beach”, which was run by Roland West. The Reno was in the downstairs of the building, with the Nile Club upstairs.

In the early days, there was live music with calypso bands, including the tenor sax player and band leader Lord Kitchener, and the West Indian cricketer Clive Lloyd was a regular visitor.

In 1986, the Reno and the Nile closed their doors. The building was demolished in 1987, with the council declaring them unsafe. The site was later excavated in 2017 as part of an archaeological project to preserve the memories and artifacts of the iconic venues.

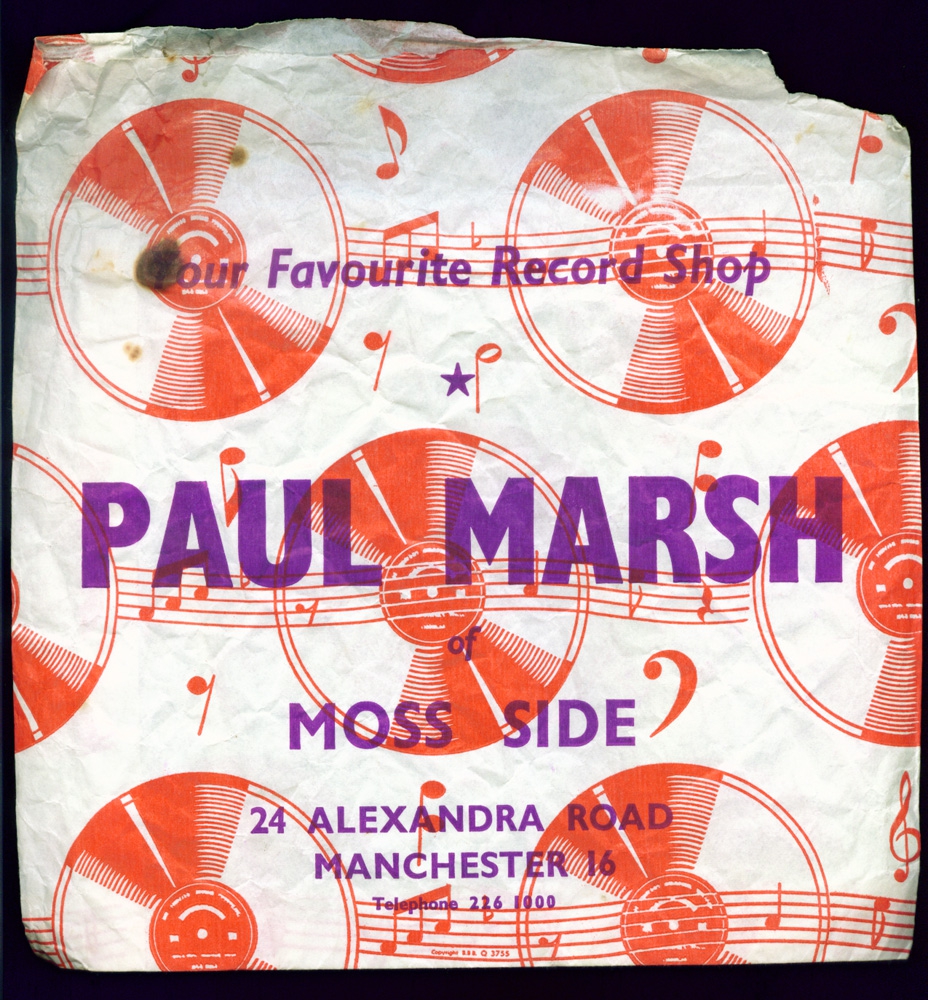

The Reno and the Nile were part of a thriving music scene, with record shops springing up in the area, acting as hubs for people to gather, listen to music, share culture and feel connected to their communities. This included Murray Records, a landmark further down Princess Road, and Paul Marsh on Alexandra Road, catering mostly for people looking for the latest Jamaican releases.

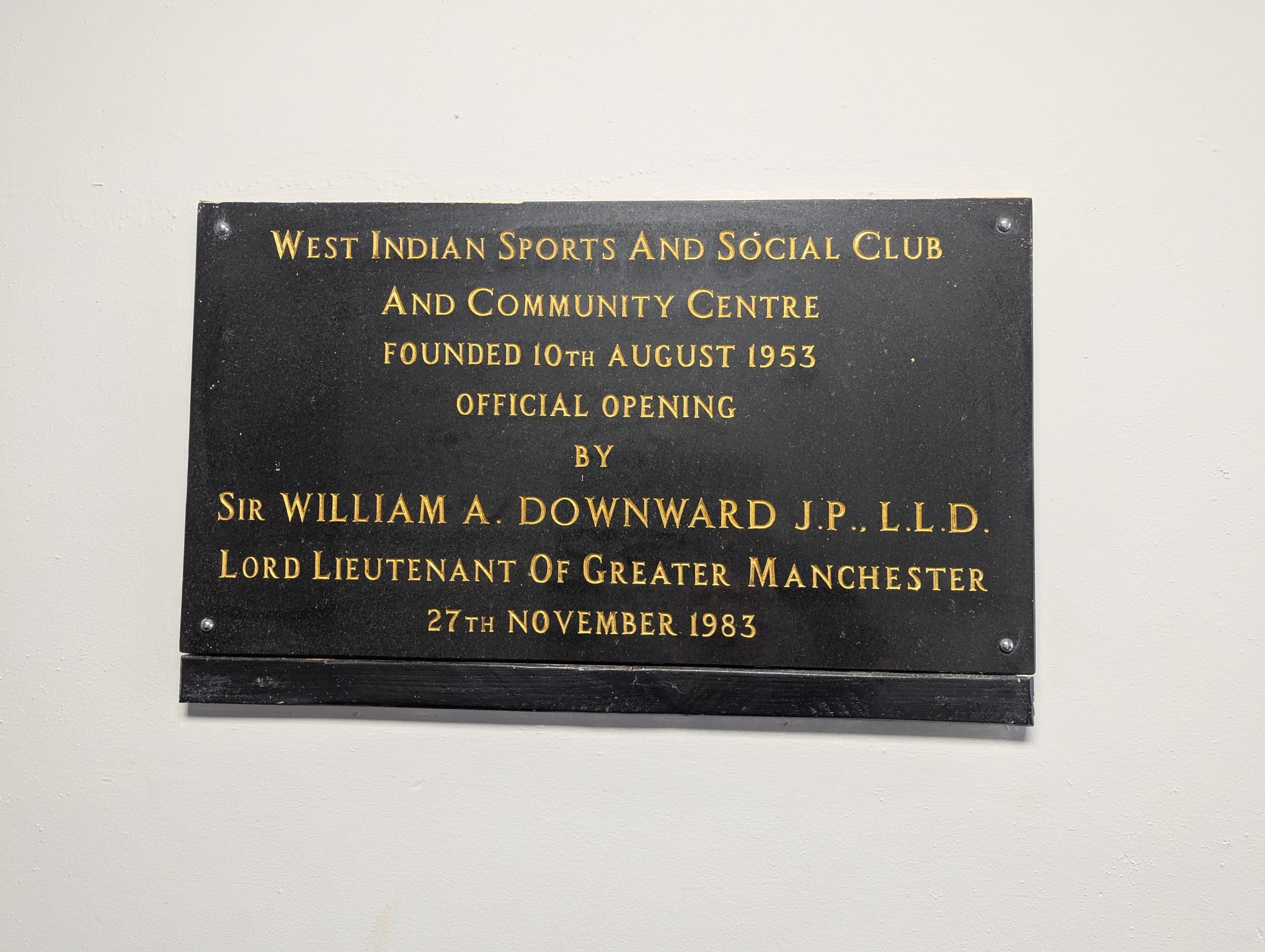

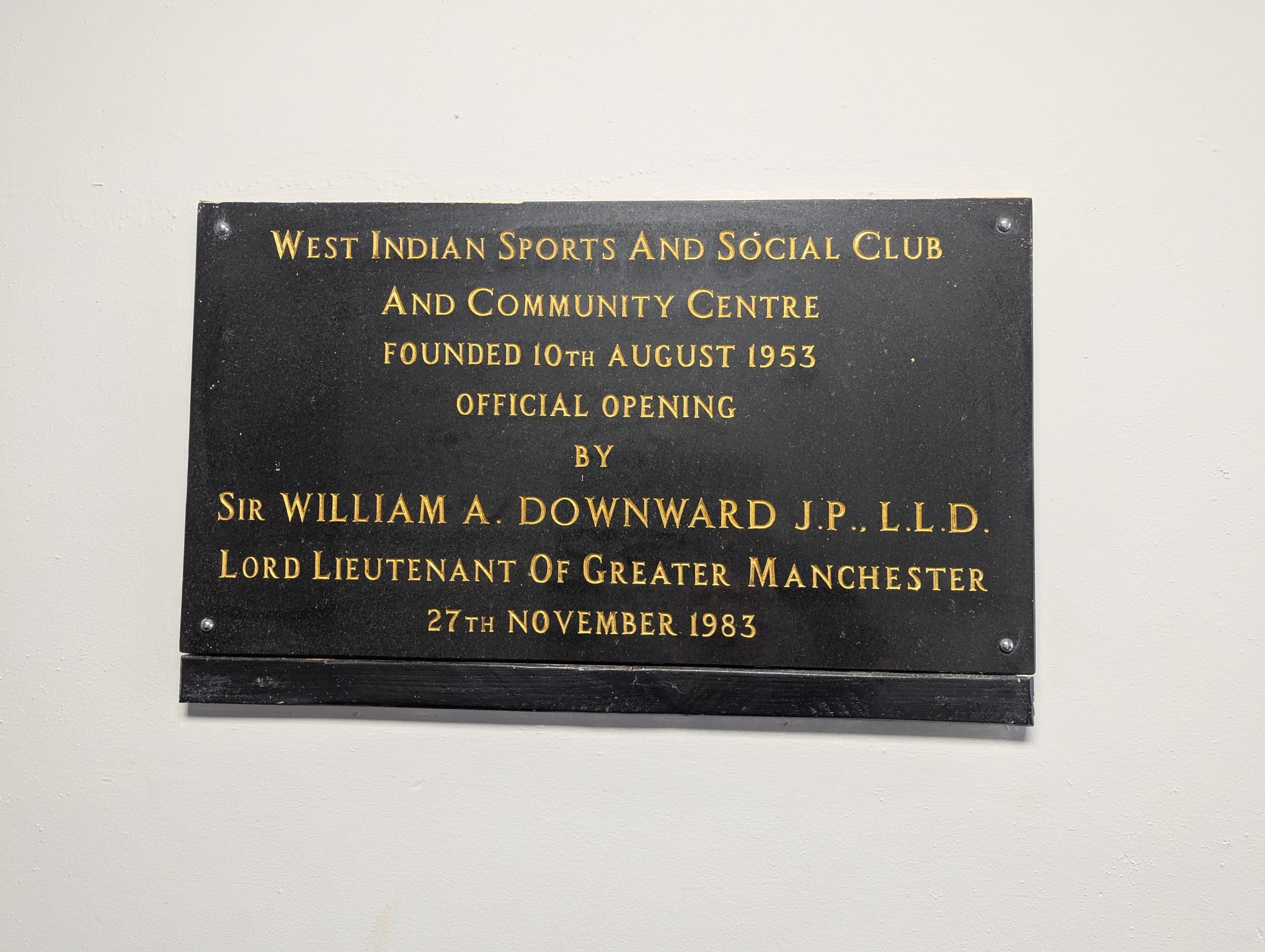

Stop 14: West Indian Sports and Social Club

The West Indian Sports & Social Club (WISSC) was created in 1953. Since that time, the WISSC has maintained its presence in Manchester as the only membership-led community self-help group dedicated to providing a focal point for the Windrush generation.

The WISSC founding members included Ashton Douglas, Ashton Gore and Euston Christian. All three men served in the RAF and fought in the 2nd World War.

The University of Manchester Professor Arthur Lewis, who in 1979 was awarded the Noble Memorial Prize for his contribution to the field of economic development, was also involved in the development of the WISCC.

He and WISSC created an evening class centre in Hulme to support many of the Windrush generation with literacy and numeracy needs. This centre was funded by Manchester City Council.

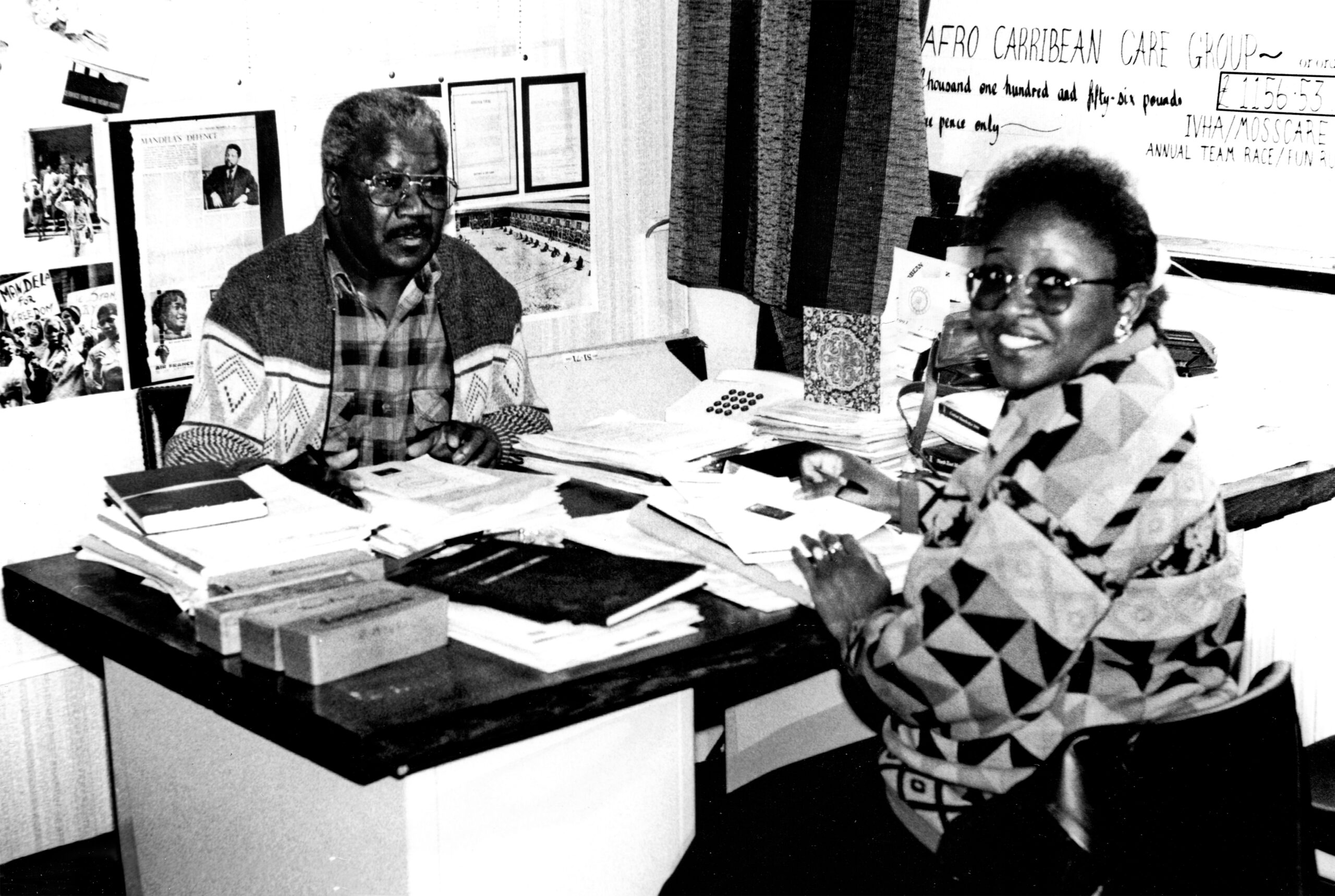

Stop 15: Mosscare and Great Western Street

A group of volunteers set up Moss Care Housing in the 1960s, with (rumour has it) £5 donations from five churches to register as a housing association, hence its first name – United Churches.

It was first based in St James Church and still has an office on Great Western Street. It worked with the council to retain and refurbish homes in Moss Side, as an alternative to demolition as part of the slum clearance.

In 2017 it merged with St Vincent’s Housing Association and is today known as MSV.

Until the 1960s, Great Western Street ran from roughly Withington Road all the way to Wilmslow Road, and was one of the longest roads in Manchester. However, the area from Withington Road to here on Princess Road was part of a programme of ‘slum clearance’.

The clearance was the focus of the Moss Side Housing Action group and Moss Side Tenants’ Union campaigns – to fight for low-rise housing and for everyone to be rehoused, regardless of their tenancy status.

It is partly down to these campaigns that the Alex Park estate was rebuilt as low-rise housing, and the area between Princess Road and Wilmslow Road was not cleared.

Stop 16: Robert Lizar Solicitors

Since its foundation in 1978 Robert Lizar Solicitors has provided representation for those who have protested against injustice, discrimination, and the destruction of our environment.

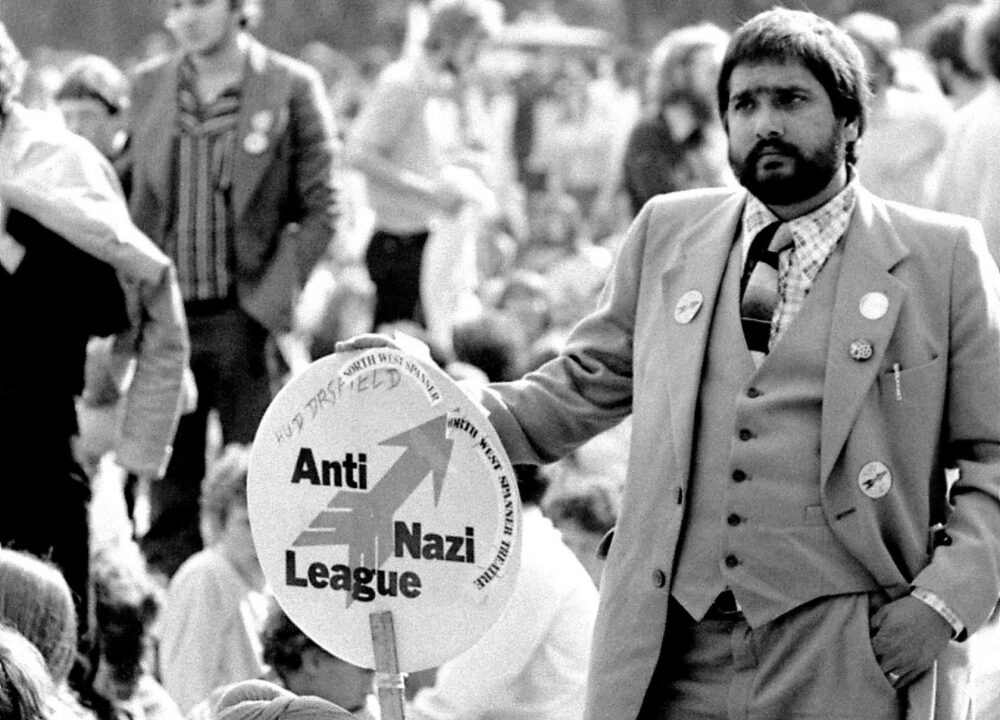

They have represented those campaigning against racism and hatred from the 1970s to the present day, whether the protest has related to actions of Government or major institutions or the actions of Neo-Nazi parties. They represented those in the local community arrested during the uprising of anger against injustice, discrimination and police brutality, described in the media as the Moss Side Riots of 1981.

Robert Lizar has represented members of the National Union of Mineworkers and their supporters during their struggle to save their jobs and their communities during the strike of 1984-5, and represented those who were sanctioned by outdated and homophobic legislation against the LGTBQ community, including successfully challenging discriminatory criminal prosecutions in the European Court.

Stop 17: The Phil Martin Centre

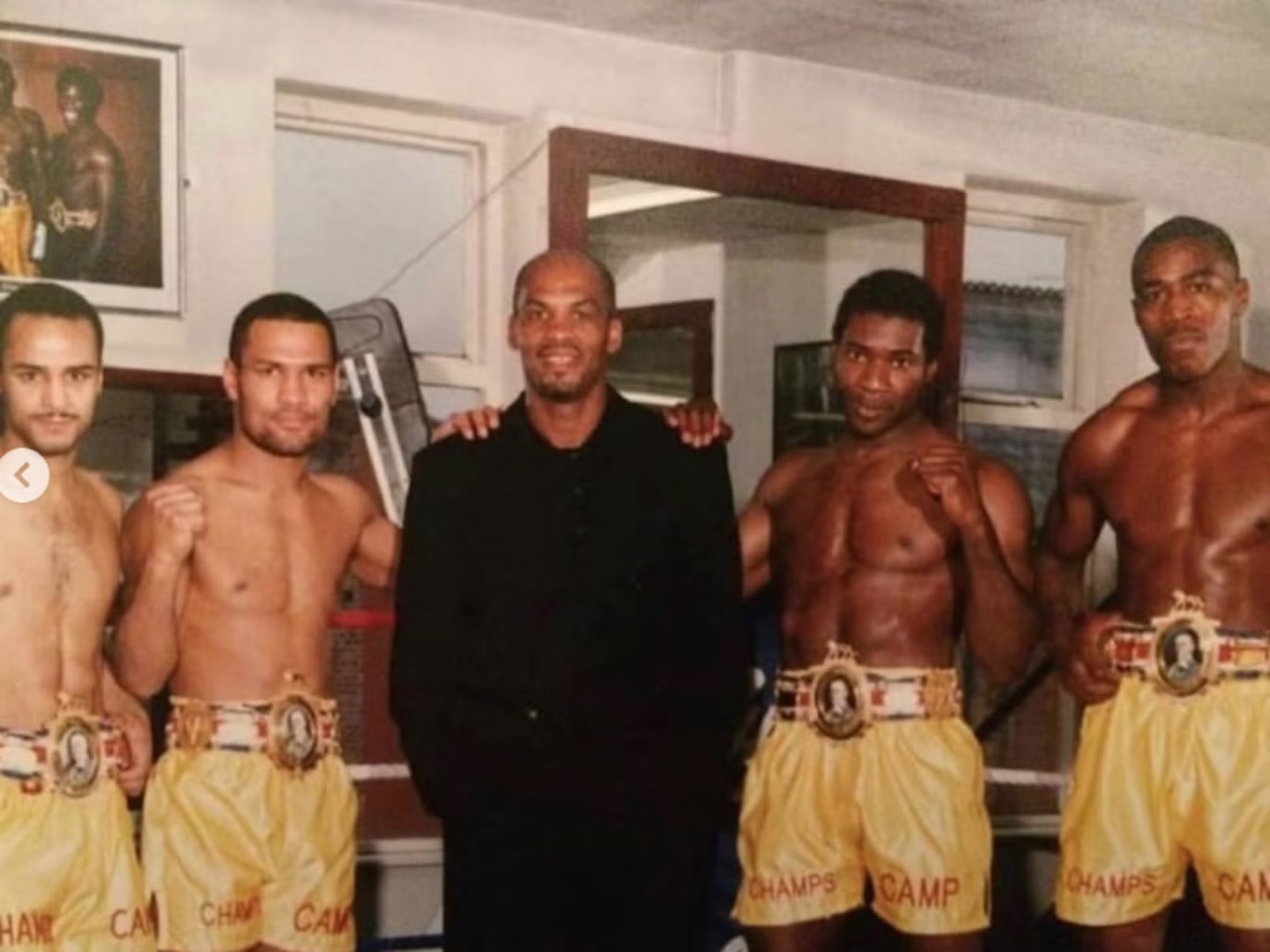

Phil Martin was an English professional light-heavyweight boxer born in Moss Side.

Phil started a boxing club for local young people after the riots in 1981. He did this without any financial or public sector support, apart from help from the Co-op, who let him use derelict rooms above their store. He became the first Black person in Britain to become simultaneously a registered professional boxing coach, manager and promoter.

Initially, he created a very successful amateur boxing club and then, with a capital grant from Sport England, made a purpose-built boxing gym, with the help of people who used the gym, some of whom were tradesmen, and local young people as labourers.

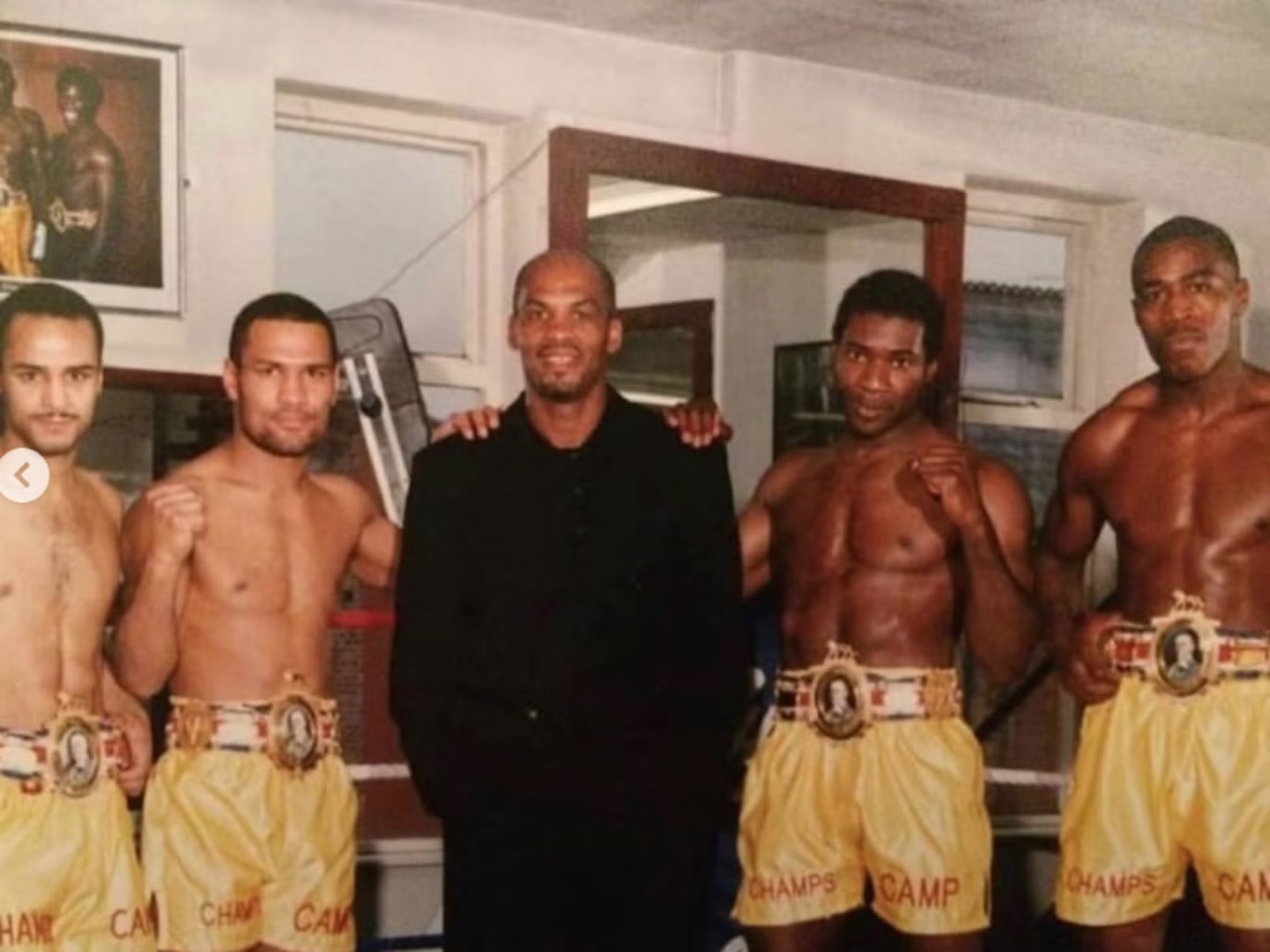

By the end of the 1980s, the gym was recognised throughout the country as producing top class boxers, the best of whom turned professional under the ‘Champs Camp’ brand.

Over the next 10 years Phil built the most successful amateur and professional boxing camps in the UK and by 1993 he had four professional British Boxing Champions, Maurice Core, Carl Thompson, Frank Grant and Paul Burke.

Stop 18: Alexandra Park

Alexandra Park was developed by Manchester Council in 1870.

Keir Hardie organised the first known Independent Labour Party May Day rally in the park on 2 May 1892, attracting about 60,000 people.

The park was the venue for the great Manchester Women’s Suffrage Demonstration of 1908, with a procession from Albert Square, and other suffrage demonstrations. In 1913, suffragette Kitty Marion planted a bomb that damaged the cactus house.

After Enoch Powell attempted to campaign in the park against immigration in 1960, Rock Against Racism organised several events in the park, including one in 1978 featuring Steel Pulse and Buzzcocks.

The Park has hosted the annual Caribbean Carnival since 1971, when a group of locals of mostly St Kits & Nevis and Trinidadian origin decided to throw an impromptu procession through the streets, just like they used to back home.

Every year since, traditional bands, dance troupes and floats have formed a parade that snakes through Hulme and Moss Side on the Saturday of carnival weekend.

Stop 19: Nello James Centre

The Nello James Centre was bought with funds donated by Vanessa Redgrave and donated to the community. It started in 1967 as a community education centre, the cottage supplied day-care and a nursery playground, legal advice, a printing workshop and a social centre.

The founders of the centre had partly come together to protest police brutality, although its membership broadened beyond West Indians to include local university students.

Among its successful events were dance nights and a free university. The centre was visited by the select parliamentary committee on race relations.

Its political radicalism was expressed not only in the cottage being named after leading Trinidadian socialist intellectual C.L.R. James but also in the posters on the trees outside reading ‘Free Angela Davis’. Angela had been arrested as part of the repression of the Black Panther Party in California during the early 1970s.

The Nello James Centre was the base for Walton Trust, started in 1978. It organised a range of activities in support of the local African Caribbean community, including a day nursery, advice centre, educational support, social groups and housing support. Active members of the Walton Trust developed several initiatives – The Trust established the Neil Pearson day nursery in 1971, named after one of their trustees; and Sojourners House Women’s Refuge was set up in 1991 to provide short-term accommodation to meet the growing need for Black women and children to have safe, temporary accommodation when escaping domestic violence. By 1990 Walton Trust had 65 homes in the area.

Meanwhile, in answer to the Moss Side uprising of 1981, Arawak Housing Association was created thanks to the vision of the inspirational Louise DaCocodia, who was passionate about satisfying the housing needs of the African Caribbean Community. In 1987 Arawak Housing Association registered with the Housing Corporation and appointed Louise as its first chair.

In 1994, Arawak and Walton merged to become Arawak Walton Housing Association. The association has grown and prospered over the years by offering an excellent, culturally sensitive and personal service to its diverse residents.

Stop 20: George Jackson House

George Jackson House was a home for children experiencing homelessness set up by Kath Locke and Ron Phillips in 1973.

Stop 21: The Windrush Millennium Centre

The Moss Side Community Development Trust was developed by Hartley Hanley, Gerry Wheale, Sandra Bitaye, Micky Bisson and Chris Woodcock. It was initially based in Portacabins on Moss Lane East, next to Hydes Brewery.

Job Link was also based at the Trust, providing training for unemployed people. They secured funding to work with the Somalian Community following a big migration into the area.

After securing funding from the National Lottery, MSCDT built the Windrush Millennium Centre, which has been providing services to Moss Side, Hulme and the surrounding areas for more than 25 years.

If you pop into the Windrush, you’ll find a great display of pictures of Old Moss Side!